In sheer dollars, abortion rights supporters in Alabama had the upper hand.

They came with deep pockets to fight a constitutional amendment guaranteeing that the state constitution would not cover abortion as a protected right.

In all, abortion rights supporters spent about $1.4 million trying to defeat that amendment compared to just about $8,000 spent by their rivals.

In the end, the amendment won handily. It received 59% of the vote in 2018.

But this was Alabama, where opposition to abortion is an embedded part of the political culture and large sums of cash were unlikely to make a difference.

“If you’re going to fight for abortion rights in Alabama, you’re going to need a lot more than money,” said Glen Halva-Neubauer, who studies abortion politics at Furman University. “I just think you’re on super, super hostile ground.

“At some point, there’s a limit to money,” he said.

If other states — such as Alabama — are any indication, Kansans can expect to see millions of dollars flowing into the state next year, when voters will be asked to approve a similar constitutional amendment to ensure abortion is not a protected state right.

And money might not matter as underscored in Tennessee and Alabama, where millions were spent opposing such amendments only to see them prevail.

Since 2014, voters in Tennessee, West Virginia, Alabama and Louisiana have passed constitutional amendments that ensure abortion is not a protected right.

Next up is Kansas, where voters next will get the chance to reverse a state Supreme Court ruling that found a woman’s right to an abortion is protected by the Kansas Constitution. The election is now less than a year away.

The campaign will come at a critical moment in the abortion debate, with the U.S. Supreme Court expected to decide a case in which the state of Mississippi is asking the high court to overturn Roe v. Wade.

And who’s to say what a campaign in 2022 might look like if the COVID-19 pandemic isn’t curtailed significantly by next year.

Supporters of the amendment — known as “Value Them Both” — are already expecting an onslaught of out-of-state money similar to what’s been spent elsewhere to defeat similar proposals. They are planning to counter with a concerted ground attack.

“We fully expect the abortion industry to try to buy this election like they’ve tried to do in other states,” KFL Executive Director Peter Northcott said shortly after the Legislature approved the amendment.

“To offset that, we’re going to take our message directly to voters. It’s going to be a lot of door to door, a lot of shoe leather ensuring that we can counteract what they’re probably going to see over the airwaves.

“I think voters in Kansas can anticipate seeing the largest grassroots mobilization in Kansas history, and that is not just bluster.”

Rachel Sweet, regional director of public policy for Planned Parenthood Great Plains, said abortion rights opponents should not be seen as the little guy in the campaign ahead.

“I resist any narrative that paints Kansans for Life as the underdog in this fight,” Sweet said in an interview earlier this year after the Legislature put the constitutional amendment on the ballot.

“They have had a tremendous amount of control of the state Legislature for well over a decade and have a great deal of political influence and resources to bring to bear.”

Any notion that abortion rights supporters are going to “buy” the election is “mind boggling,” she said, given Kansans for Life’s influence within the state.

“Having people at doors and on phones for much of the next 15 months is going to be a critical part of this campaign,” she said earlier this year.

“It’s not just: Are we buying enough mail, digital and TV and sending it to the right places?” she said.

“We’re going to be having conversations with voters before any of those larger expenditures start happening,” she said.

There are already signs that the campaign is in the earliest stages, with Kansans for Life already buying social media ads in June that promoted the Value Them Both Amendment.

At the end of July, Kansans for Life hosted a Facebook Live event to discuss the background of the constitutional amendment.

And later this this month in Bonner Springs, KFL is holding an event featuring Republican gubernatorial candidates Derek Schmidt and Jeff Colyer.

KFL’s political action committee will conduct a straw poll asking people attending the event to vote for the candidate who inspires them most to talk about the amendment.

Meanwhile, abortion rights supporters are conducting polling, raising money and ramping up their staffing as they head into next year.

The elections have played out differently depending on the state, with the results in some states much closer than others.

Kansas is an outlier because the referendum will be on the August primary ballot, which will likely be dominated by Republican primaries that are expected to draw out more voters who oppose abortion.

Interviews with those involved in amendment campaigns start to reveal some trends that may be seen in Kansas and something to look for here. They include:

Money not so important

In states that track campaign spending on issue-related campaigns, money was not necessarily a factor.

Like in Alabama, abortion rights supporters spent much more than their opponents in Tennessee and still lost in 2014.

Alabama was always an uphill fight, some experts said.

“Abortion is not an issue that gets talked about a lot in political discourse in Alabama. By that, I mean that it is not heavily debated,” said University of Alabama political scientist Richard Fording.

“Every Republican is pro-life and the few Democrats who get attention rarely ever mention it because they know that supporting abortion is politically costly,” Fording said in an email.

The Tennessee constitutional amendment passed with about 53% of the vote, even though abortion rights supporters spent $4.5 million campaigning against the amendment.

About $2.4 million was spent campaigning for the amendment, which said that nothing in the Tennessee constitution protects a right to an abortion.

The Tennessee campaign featured a heavy dose of TV ads on both sides, with no less than nine different groups campaigning for or against the measure.

Big contributors to the campaign for the Tennessee amendment included former Republican Tennessee Congresswoman Diane Black and her husband, who each gave $250,000 to the efforts.

Former Republican Gov. Bill Haslam and his wife kicked in $10,000 each, while the conservative group Susan B. Anthony List gave $20,000.

Tennessee pharmaceutical executive John Gregory gave $150,000 to the campaign, and National Right to Life gave $15,000. Grace Chapel of Franklin gave nearly $16,000.

Other churches from across Tennesee – Catholic, Baptist and United Methodist – chipped in anywhere from about $100 to $5,500, campaign reports showed.

On the other side, Planned Parenthood of Middle and East Tennessee put at least $500,000 into the campaign along with Planned Parenthood of the Great Northwest in Seattle, which gave at least $750,000.

The campaign against the amendment also received hundreds of thousands of dollars more from other Planned Parenthood affiliates across the country, including chapters in Florida, California and Massachusetts that funneled at least $550,000 into the campaign.

Louisiana was an exception where abortion rights opponents spent more than their rivals and won with 62% of the vote.

But Louisiana is different because opposition to abortion cuts across party lines and racial demographics.

The amendment was authored by a Democratic lawmaker and supported by Democratic Gov. John Bel Edwards, who two years ago was the only Democratic governor who opposed abortion.

“The pro-choice folks, when it comes down to money, they’ve got people with money,” Halva-Neubauer said “That doesn’t necessarily equal votes.

“Are they going to start a super grassroots, knock-on-doors type of campaign, or are they going to rely on messaging?” he said.

Ben Clapper, executive director of Louisiana Right to Life, said it’s easy to misjudge the effectiveness of abortion opponents just because their coffers aren’t as deep.

“The bases and the structure of communities in churches allow for a systematic grassroots effort that’s not necessarily expensive,” he said.

Opponents of the Louisiana amendment “didn’t receive enough to overcome the natural proclivity of Lousianans to the pro-life cause and the solid organizational grassroots structure that we had in place already,” he said.

Supporters of the Louisiana amendment — the Louisiana Pro-Life Amendment Coalition — spent about $734,000 on their campaign.

Two groups opposing the amendment — the New Orleans Abortion Fund and Louisiana for Personal Freedoms — spent about $257,000.

In West Virginia, Wanda Franz, president of West Virginians for Life, said her organization relied heavily on billboards, direct mail and social media.

Her organization, she said, deliberately stayed away from television and radio.

“TV and radio go to too many people who don’t agree with us,” Franz said. “We aimed to go under the media and find people on the ground.”

For instance, Franz said her group and its chapters staffed festivals across the state as it tried to get word out about the amendment.

“Ours is a very much a grassroots kind of approach, and it’s not a costly approach.”

Franz said West Virginians for Life focused its efforts on its network of supporters, including churches and a mailing list of more than 100,000 people.

“With a small state like this, that’s a large part of the voters that are out there,” she said of the importance of the group’s mailing list.

West Virginia doesn’t track spending in issue-related campaigns, but abortion rights advocates estimated spending more than $1 million fighting the amendment.

Susan B. Anthony List, which donates to candidates who oppose abortion, spent $500,000 on a campaign supporting the West Virginia amendment.

Susan B. Anthony List parted ways with West Virginians for Life, spending money on a campaign that included television, radio and digital ads as well as mail.

It also had a team of more than 75 canvassers who visited 50,000 voter households during the campaign.

Margaret Chapman Pomponio is executive director of WV Free, which advocates for abortion rights in West Virginia.

Chapman Pomponio said it’s a matter of “pulling out all the stops” if the Kansas amendment is going to be defeated.

“The groups on the ground that are fighting this are going to need all the investment they can summon from state-based folks and certainly national organizations,” she said. “Hopefully, they’ve already started.”

There was a similar view expressed in Tennessee, where supporters of the amendment started raising money a year ahead of time.

For instance, the “Yes on 1” committee — the primary group supporting the amendment — raised about $59,000 by March 2014, eight months before the election.

Opponents of the Tennessee amendment — the “No on 1” committee — raised about $4,000 by March 2014, although they went on to vastly outspend their rivals in the latter stages of the election.

“You’ve got to get ahead of the rush,” Chapman Pomponio said.

“They say early money is the most important because it will demonstrate that the fight is worth investing,” she said.

Chapman Pomponio said she still reflects back on the election, in which the West Virginia amendment won 52% to 48%, or by about 20,000 votes out of 574,000 votes cast.

“Given the fact that it was so close, I am convinced that if we had more time and money to do greater public education and voter outreach, we would have easily won.”

Urban versus rural

The constitutional amendments have tended to succeed more in rural area of states than urban areas, election results show.

Even in Alabama, where the amendment won decisively, it was not as successful in the state’s urban areas.

The amendment lost in three of Alabama’s five most populated counties, defeated in areas such as Birmingham, Huntsville and Montgomery.

In Tennessee, the amendment lost in urban centers such as Memphis, Nashville and Knoxville.

It did win, however, in suburban areas outside of Nashville, such as Rutherford and Williamson counties.

“In Tennessee, most large urban areas had a slim majority of support for opposing (the amendment), but large majorities of voters elsewhere in the state voted yes,” said University of Tennessee political scientist David Folz.

Similarly in West Virginia, the amendment lost in the Charleston, Morgantown and Huntington areas but won in the other populated areas of Parkersburg and Martinsburg.

Even in Louisiana last year, the amendment lost in two of the state’s three most populated parishes that are homes to Baton Rouge and New Orleans.

The amendment prevailed in Louisiana’s three other largest parishes that are home to Shreveport, Lafayette and the suburbs west and north of New Orleans.

Francie Hunt, executive director of Tennessee Advocates for Planned Parenthood, said efforts to oppose the amendment had support from faith leaders, although it didn’t prove effective in rural areas of the state.

“We had a pretty strong and powerful base of support to fight the amendment by faith leaders,” Hunt said.

“And yet, I don’t think a lot of those faith leaders were able to elevate those voices in the rural areas, and that probably would have been very impactful,” she said.

At one point in Nashville, two groups of faith leaders held dueling news conferences within hours of each other on opposite sides of the amendment.

Another group of 40 Memphis-area pastors came out against the amendment, saying it would clear a path for the state to enact laws severely restricting abortion.

Tennessee’s three Catholic bishops supported the amendment, and Catholic, Southern Baptist and Assemblies of God denominations distributed pamphlets and spoke in favor of the proposal.

Polls done in the weeks leading up to the Tennessee election showed the amendment passing — albeit barely.

One poll done by Middle Tennessee State University a couple weeks before the election showed the amendment with support from 39% of registered voters, opposition from 32% and 15% undecided.

Another early poll commissioned by Family Research Council Action showed 50% of likely voters in Tennessee would support the measure.

Stacy Dunn, director of the Knox County Chapter of Tennessee Right to Life, said the Tennessee effort to pass the amendment came down to street-level campaigning.

“We had a great help in the churches and the civic organizations who took an interest and a passion in what the amendment would do,” Dunn said.

“They were the ones who carried the success of the amendment on their backs.”

Communications

Campaigns on both sides of the issue said voters had trouble understanding what the amendments in their states did. Did they ban abortion? Did they allow abortion? Did they give lawmakers the ability to regulate abortion?

“I think it’s very important for leaders in these campaigns to understand very closely the language that will be on the ballot,” said WV Free’s Chapman Pomponio said.

“Constitutional amendments can create anxiety. What advocates may think is straightforward language doesn’t translate that way for the everyday voter,” she said.

“It’s incumbent on them to break it down to educate statewide and engage in all the methods of public education that they can.”

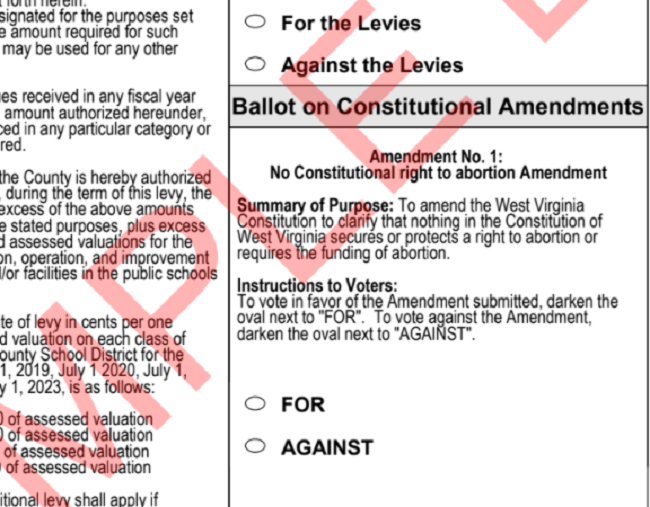

The abortion amendment in West Virginia said that nothing in the state constitution “secures or protects a right to abortion or requires the funding of abortion.”

Yet there seemed to be concern that voters were confused.

“We just really felt like it was so confusing, people didn’t know how to vote,” Franz said.

“They knew what they wanted but didn’t know how to vote for it.”

The West Virginia amendment addressed a state Supreme Court ruling that said less affluent women had the right to an abortion with Medicaid funding.

Supporters of the amendment say it was deliberately misportrayed as a measure that would ban all abortions in West Virginia.

They said the amendment would let the Legislature make decisions about regulating abortion.

Critics said the amendment undercut abortion rights by making it impossible to challenge new abortion laws under the state constitution.

A similar concern about confusion was expressed by abortion rights supporters in Tennessee over that state’s amendment.

The Tennessee amendment said that nothing in the state constitution secures or protects a right to abortion or requires the funding of an abortion.

The amendment also included this language:

“The people retain the right through their elected state representatives and state senators to enact, amend, or repeal statutes regarding abortion, including, but not limited to, circumstances of pregnancy resulting from rape or incest or when necessary to save the life of the mother.”

Hunt, from Planned Parenthood in Tennessee, said she thought the electorate struggled with understanding the implications of the abortion amendment.

“I think the amendment language was very difficult for people to understand,” she said in an interview earlier this year.

Hunt said she didn’t think voters understood that amendment gave the Legislature the power to restrict or ban abortion for any reason.

“I don’t think that was clear from the way the amendment is written.”

The Kansas campaign

Kansas is very different from the other states that have passed the amendment during general elections in the fall.

It’s anticipated that the Kansas amendment will have a distinct advantage because the election will be held in August, when the GOP will have many more primaries on the ballot and conservative turnout will be higher.

A Republican primary for governor, multiple GOP primaries for statewide office and many Republican state legislative races will likely boost conservative turnout that will likely support the amendment.

It also potentially would allow supporters of the amendment to piggyback on the Republican money spent at the top of the ballot to get out the vote, as well.

Halva-Neubauer said the path to defeating the amendment — without making a prediction — could hinge on mobilizing Republicans in bluer parts of the state who are disenchanted with the party’s direction.

“They are like the white tigers of the world, quite the endangered species,” he said.

“I think that there are still some number of pro-choice Republicans,” Halva-Neubauer said.

“If you couple that with a more general disillusionment about where the Republican Party is going and you see this as one more example of that and you can raise it to that kind of level, that might raise the stakes,” he said.

Democratic state Sen. Ethan Corson, former executive director of the Kansas Democratic Party, echoed a similar theme while pointing out the advantages the amendment will have since it’s on the primary ballot.

“I think there’s going to have to be a massive effort to talk to moderate Republicans, unaffiliated voters and Democratic voters who may not have another reason to go out and vote,” Corson said.

He called the timing of the amendment “very purposeful.”

“It was obviously meant to be at an election when turnout would be disproportionately conservative,” Corson said.

In all likelihood, there won’t be a lot of Democratic primaries on the ballot, making it important to give Democrats a reason to vote in the primary, he said.

“For a lot of Democrats, they may view it as there’s nothing on the ballot that they need to go vote for,” he said. “That’s going to be the challenge.”

But supporters of the amendment may not have it as easy as it appears.

It’s possible the U.S. Supreme Court could render a decision in a Mississippi abortion case that has distinct implications for Roe v. Wade in the middle of the campaign.

Last spring, the court agreed to hear the case over an abortion law that bans most abortions at the 15th week of pregnancy.

It could be the first time the court upholds an abortion ban before the point of viability, when a fetus can survive outside the womb.

The state of Mississippi is now urging the high court to overturn Roe and allow states to decide how to regulate abortion.

The case is on track to be heard this fall with a decision due in the spring or summer, right in the middle of the campaign on the Kansas amendment.

Halva-Neubauer said the court’s decision in the case could serve to energize Kansas voters if they believe the amendment would lead to a ban on abortions.

“If you say there is no option, I don’t know,” he said.

“I think that swings the pendulum, it gets at individual liberty, it brings out the libertarian kind of impulse in the American psyche and the American voter.

“I think that could not necessarily redound to the benefit of the pro-life movement.”

A Kansas Republican consultant, speaking anonymously to be candid, said a decision in the Mississippi case could complicate matters but wouldn’t matter in the long run.

“The Mississippi case’s timing, probably more than the substance of the ruling itself, will certainly spark a lot of discussion in the media and hand-wringing by folks involved in the campaigns,” the consultant said.

“But, at the end of the day, I don’t think the ruling ultimately changes the fundamentals of the campaign for or against the constitutional amendment,” the consultant said.

Kansans for Life thinks the Mississippi case plays into its campaign.

“The more the federal case comes into focus for the public, the greater that spotlight is going to be on the abortion industry’s extreme position,” said Danielle Underwood, spokeswoman for Kansans for Life.

“This whole thing is going to be a big educational process for the people of Kansas,” Underwood said.

“They are already learning that regardless of what happens in this case, that unlimited abortion practices are here now and going forward unless the people approve the Value Them Both amendment,” she said.

Corson said he thinks voters already understand the enormity of what’s at stake with the amendment regardless of the Mississippi case.

“I do think a lot of folks…already have a heightened sense of urgency about this,” he said. “It would definitely make the stakes more real.”

Sweet from Planned Parenthood said earlier this year that polling had already been done to get an idea how the electorate views the issue.

“I think we know which parts of the electorate are solidly in our camp and who is persuadable,” she said.

Brittany Jones, director of policyand engagement for Kansas Family Voice, said she believes Kansans want the amendment to pass regardless of how much is spent in the campaign.

“I imagine it’s going to take a lot of money and a lot of effort and energy (to pass the amendment), and we’re prepared to do that,” Jones said earlier this year.

“When it comes down to it, Kansans — no matter how they identify themselves — don’t want unlimited abortion to come to Kansas,” she said.

“I think that crosses the political spectrum.”