It’s one thing to create new jobs.

It’s another to fill them.

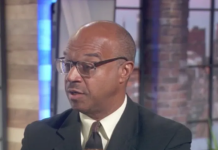

As much new investment as Panasonic, Amazon and Kiewit might bring to Kansas, Lt. Gov. David Toland says employers are still struggling to fill jobs.

“We don’t have enough human beings in the state to keep up with the economic growth that we’ve had,” said Toland, who doubles as the state’s commerce secretary.

The state’s population growth is stagnant and new college graduates are leaving Kansas, two factors that complicate the state’s ability filling new jobs.

About 84,000 people left Kansas from 2021 to 2022, according to census data. Many left for Missouri, Oklahoma, Florida, Texas, California, Colorado or elsewhere.

Kansas gained about 2,700 people over the first three years of the new decade for an increase of about 0.1%. The state ranked 34th in population growth from 2020-2023.

Many of those migrating out of state are young adults who graduated from Kansas universities but decided to take their skills elsewhere.

In 2022, about 12,800 Kansas college graduates, many with degrees in business or management, agriculture, engineering or health care, were working outside the state.

“We’ve got to stop the bleeding and stop losing our educated young talent,” he said.

Kansas is now fighting to win those native Kansans back.

The Commerce Department on Monday launched a new campaign – titled “Love, Kansas” – that targets expats with the goal of luring them back to the Sunflower State.

“We’re not trying to target folks that have lived in Connecticut their whole life and say, ‘Hey you should move to Kansas,'” Toland said in an interview.

“We’re going after people who already know Kansas on some level, but who may not know how much momentum we’ve achieved as a state,” he said.

The goal of the campaign, funded by a $2 million appropriation from the Legislature, is for Kansans to reach out to people they know in other states and sell them on Kansas attributes that might lead them back home.

“This is about the person-to-person engagement,” Toland said.

The Commerce Department is working with state universities to identify where clusters of their alumni now live, places such as Dallas, Chicago and northwest Arkansas.

“We’re letting the data drive us,” Toland said of identifying clusters of native Kansans.

“It’s a lot harder in many cases to get somebody to move from New York City back to Kansas,” Toland said.

“But people who have stayed in the Midwest are more apt, we think, to be able to do a relocation back home,” he said.

The agency is partnering with 19 cities across the state to help bring some of their residents back home, including Overland Park, Miami County, Dodge City, Manhattan, Wichita, Salina, Topeka and Pittsburg.

Officials said the first 50 communities to partner with the Love, Kansas campaign will be eligible for a $5,000 grant to assist efforts in attracting new residents to their city.

The money is to be used for expenses for hosting Love, Kansas events or Love, Kansas marketing.

Kansas is the latest state to market itself to the rest of the country in an effort to combat population loss and build its workforce to fill open jobs.

Two years ago, then-Republican Nebraska Gov. Pete Ricketts launched a national marketing campaign to promote the state as a quality place to live, work and raise a family.

The state spent $10 million on an advertising campaign using federal coronavirus relief money that aired in television markets within 500 miles of Nebraska, including Minneapolis, Kansas City, Denver and Chicago, as well as in Austin and Silicon Valley.

Last year, Michigan started a $20 million national marketing campaign to combat the state’s flat population growth by attracting and retaining young talent.

The campaign included television, radio and online advertisements in 11 states. It was portrayed as the largest state-led talent attraction effort in the country.

In Ohio, the state’s private economic development arm, JobsOhio, posted billboards in coastal cities across the country promoting the Buckeye State.

The Columbus Dispatch reported that JobsOhio doubled its marketing budget to $25 million to pay for the campaign, although it allowed for the possibility the initiative could be pulled back if didn’t produce benefits.

The recruitment effort put up billboards in New York City, Seattle, Boston, Chicago, San Francisco, Austin and in Washington, D.C.

The agency put up a billboard in Seattle that read: “Live where you can actually save for a rainy day.”

Another billboard in Boston near Fenway Pak read, “0% corporate tax rate? That’s the ticket.”

Toland said the goal of the Kansas campaign is to appeal to native Kansans with shifting priorities.

He said people living in more metropolitan areas can grow weary of the cost of living, traffic and other pressures that come with big-city living that might make people receptive to a different type of lifestyle.

Toland holds himself out as an example of someone who “boomeranged” – left the state after graduating from college but later decided after starting a family that maybe living in a large urban area on either coast wasn’t what it once was in his 20s.

“What might be exciting to someone in their 20s can be a headache when they’re in their 30s. Our priories change,” he said.