In nearly 30 years, not much has changed for Republican women in Congress.

In the 101st Congress from 1989 to 1991, there were 13 Republican women serving in the House.

Twenty-eight years later, Republican women in the House still number 13.

While a record number of women are serving in Congress this year, an overwhelming majority are Democrats.

Even as Democratic women won in record numbers, Republican women were headed the opposite direction.

Their numbers plummeted to 13 this session from 23 during 2017-18 when several Republican women – Barbara Comstock in Virginia and Claudia Tenney in New York for example – lost in swing districts.

The number could shrink even further with the retirements of Susan Brooks in Indiana and Martha Roby in Alabama when their terms end after next year.

It was the lowest number of Republican women to serve in the House since 1993-95, when 12 Republican women served in the chamber, according to the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University’s Eagleton Institute of Politics.

Now, the GOP is working to turn the corner, especially in the Kansas 3rd Congressional District, where two Republican women — Amanda Adkins and Sara Hart Weir — are lining up to take on Democratic incumbent Sharice Davids. Davids was elected in that record-setting election last year. Kansas Senate President Susan Wagle is now running for the U.S. Senate, which has eight Republican women, an increase of seven from 1989-91.

“We have the same amount of men in Congress named Jim as we have female congresswomen in the House of Representatives,” Weir said recently.

“I see this as a huge opportunity to be part of a solution as relates to putting more (female) GOP leaders in Congress,” she said.

Experts argue — and Republicans agree to an extent — that the GOP hasn’t made recruiting women a priority over the years, something that’s now starting to change.

“We’re starting to see that Republican women in the House are recognizing the problem and even Republican leaders are recognizing the problem,” said Betsy Fischer Martin, executive director of the Women and Politics Institute at American University.

It’s a concern that the National Republican Congressional Committee recognizes as it moves into the 2020 election cycle.

The GOP starts at a disadvantage because it fields far fewer female candidates then male candidates.

Last year for instance, a record number of female candidates filed to run for the House and the Senate.

Among them was Kansas state Sen. Caryn Tyson, who finished second against five men in the Republican primary for the 2nd Congressional District.

Of the record-breaking 476 women who filed to run for the U.S. House, just 25% were Republicans.

Similarly in the Senate, 22 of the 53 women who filed to run were Republicans.

“Recruiting more female candidates had been one of our primary objectives,” said Bob Salera, spokesman for the National Republican Campaign Committee.

“The Republican conference feels that it’s important that the membership represent the true diversity of Republican voters, and that includes bringing more women into the ranks,” he said.

Salera said the RNCC has already met with 200 female candidates, many of whom have already announced they are running.

“We look forward to having a slate of candidates that reflects more fully the diversity of our country in terms of women, more candidates of color and more veterans,” he said.

But that may not be so easy, experts say.

There are a number of institutional obstacles that confront Republican women, including the perception that they might lean more liberal and they don’t have access to the same fundraising infrastructure that’s available to Democratic female candidates.

“Women in general are seen as more liberal than men, so Republican women who want to run for their party’s nomination may have a harder time in these more polarized times,” said Meredith Conroy, a political science professor at California State University, San Bernardino, who has studied gender and politics.

“I haven’t seen evidence that this actually hurts their electoral fortunes,” she said. “The effect is that it probably discourages Republican women from running in the first place.”

But studies have shown a fundraising imbalance between groups such as Emily’s List that support liberal female candidates and groups such as Susan B. Anthony List that support conservative female candidates.

In 2018, Emily’s List raised more than $60 million, compared to three conservative women’s PACs that raised more than $1 million combined for Republican female candidates, according to research by Rosalyn Cooperman, a political scientist at the University of Mary Washington in Fredericksburg, Virginia.

The Emily’s List political action committee raised about $61.7 million, compared to the Republican women’s groups Susan B. Anthony List ($697,925), RightNow Women ($131,735) and Winning for Women ($466,238), according to Cooperman’s research.

Cooperman points out that women’s political groups have emerged because neither party has emphasized recruiting women over time.

Historically, “neither party has really been great at rolling out the welcome mat for women,” she said. “The whole reason that Emily’s List formed was in essence because Democrats weren’t recruiting women candidates and encouraging them to run.”

However, it has taken a greater hold on the Democratic side, which tends to incorporate many more voices than the GOP, Cooperman said.

“If you’re looking at the Republican Party, it does not like to see race, it does not like to see gender, it does not like to see sexual orientation,” she said. “If you look at the candidate pool, it’s reflected in that.”

Adkins said successful Republican female candidates need to have a mix of family belief systems, community relationships and education.

In her own life, Adkins talked about the role her father played in instilling conservative values that guided her when she chaired Kansas College Republicans and later the state GOP.

“My own father always had National Review on the coffee table, and civic responsibility (and) commitment to community was a regular topic at the dinner table,” Adkins said in an email. “When times were tough, I thought of what dad taught me about our conservative family beliefs and it gave me inspiration and courage.”

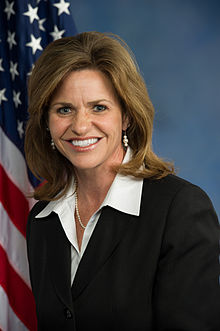

Former Congresswoman Lynn Jenkins is an example of a female candidate who succeeded in Kansas despite the obstacles female Republicans face.

She battled through a primary in 2008 to beat former Congressman Jim Ryun by about 2 percentage points and defeated incumbent Democratic Rep. Nancy Boyda by 4.4 percentage points. She cruised to reelection in four subsequent election cycles.

Pat Leopold, Jenkins’ former campaign manager and chief of staff, said the congresswoman’s professional background as an accountant and the fact that she served as state treasurer gave her a boost.

“It wasn’t easy. She had to work for it,” said Leopold, who also is advising Weir. “There is a perception that if you’re a Republican woman, you’re more moderate, and usually in primaries the more moderate person isn’t successful.”

So the Jenkins campaign tapped into fiscal responsibility as an issue that would appeal to Republican voters across the board, highlighting her work as a certified public accountant and as state treasurer.

“For Lynn Jenkins, it was being a CPA and having that fiscal watchdog background,” Leopold said. “When they think of Lynn Jenkins, they think of fiscal stewardship.”

Salera concedes that the GOP has not placed an emphasis on recruiting women, saying the Democrats have been more focused on identity politics than the Republican Party. However, he said the party recognizes the need for more diversity.

“Democrats run on identity politics,” he said. “It’s always been a big stated goal of theirs to put more women on the ballot, put more Hispanic candidates on the ballot, because they speak to the issues that the base wants to talk about.

“Identity politics has never been a strategy of Republicans, so we haven’t focused in on getting those candidates based on their background,” he said.

Indeed, others say the political left has been more skilled at reaching out to female candidates over the years than the GOP.

“The left has done a very good job of reaching into all corners of the party and tapping into potential and kind of encouraging women to run,” said Olivia Perez-Cubas, spokeswoman for the Winning for Women Action Fund, which seeks to elect Republican women to Congress. “That kind of structure is not as well formed on the right.”

Nevertheless, Salera said there’s a shift in the party’s focus.

“I am not saying we are focusing on identity politics, but I think there’s acknowledgement that we need our conference to accurately represent the diversity of our party,” he said.

“That’s where our recruiting focus is going now, and we’re actively trying to recruit more female candidates and help them build out the campaign structure they’ll need to beat Democrats next November.”

The emphasis on attracting female candidates came about in the aftermath of last year’s election.

Republican Congresswoman Elise Stefanik of New York rebranded her leadership political action committee to help Republican women win primaries.

At a news conference earlier this year, Stefanik said the country had reached a “crisis level” in the number of Republican women in Congress.

“We know this is not reflective of the American public,” she said. “We can and we must do better.”

Winning for Women, meanwhile, started a super political action committee in 2017 with the goal of electing Republican women in primaries.

The super PAC — the Winning for Women Action Fund — is shooting to elect 20 Republican women to the House in 2020. It’s already watching about 30 female candidates for 2020, including Weir and Adkins.

Perez-Cubas said the group is still watching and waiting in the Kansas 3rd District.

“It’s still very early,” she said. “They’re definitely on our radar and we’re in touch, but it depends still.”

The group brought resources to bear earlier this year to help Joan Perry win the initial Republican primary in a special election for North Carolina’s 3rd Congressional District.

Perry emerged from a field that included five men to advance to a runoff in the primary, where she lost by almost 20 percentage points to Greg Murphy.

Winning for Women dropped about $842,000 in that race on behalf of Perry, while Susan B. Anthony List put nearly $330,000 into the race.

But the news wasn’t all bad for Republican women, Fischer Martin said.

“It showed the willingness of some of these outside Republican women groups to raise money and spend money,” she said. “The fact that they were able to get involved in a serious way in North Carolina was progress on that point.”

However, the downside is that some conservative women’s PACs often don’t get involved in primaries, which is where Cooperman and others say female Republicans tend to have the most difficult time. Last year, less than half the 120 Republican women who filed to run for the U.S. House won their primary.

It’s potentially a bigger dilemma in the Kansas 3rd District, where two women are expected to run against each other in the primary.

“It’s a conundrum,” Cooperman said. “What do you do if you’re Winning for Women? If you select one compared to the other, you’ve essentially knee-capped that other woman. It’s really a challenge.”

Asked about how Winning for Women might decide an endorsement between two female candidates, Perez-Cubas acknowledged the PAC doesn’t have unlimited resources and needs to “play smart.”

“You’ve got to pick the candidate who is the best fit for her district and who’s got a path forward,” she said.

“I do think it’s important that when there is that woman candidate she gets the support she needs. I don’t think having two female candidates is a reason to not play.”

In the long-term, there’s Congresswoman Davids, who can depend on outside help from Emily’s List that will be hard for either Adkins or Weir to match.

“Emily’s List is going to help Rep. Davids raise a significant amount of money,” Cooperman said. “There’s not going to be an equivalent women’s PAC on the conservative side that’s going to do that for either woman. That’s the problem Republican women face.”